In 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court could overturn Roe v Wade, imperiling all women’s freedoms, and creating a new pipeline to prison for the vulnerable just as the world is learning how counterproductive most incarceration – solutions are. Today’s guests argue that things could have been very different if the white dominated “choice” movement had paid closer attention to all women’s choices, or lack thereof; if anti-violence advocates had rejected criminalization and incarceration as a solution to the violence in women’s lives. Things could have been different, our guests argue, if a different part of the US women’s movement had gained more attention – attention it is beginning to get now. There has always been such a movement, they know, because they were there. Today we talk to Black abolitionist feminist Beth Richie and Queer southern feminist Suzanne Pharr who have worked together, for abolition, feminism, and a systemic differently world for forty years. What have they learned? And what is their message for us now, when so much hangs in the balance?

Guests

- Suzanne Pharr, Co-founder, Southerners on New Ground. Author, Transformation: Toward a People’s Democracy

- Beth Richie, Director, Institute for Research on Race & Public Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago. Author, Compelled to Crime: the Gender Entrapment of Black Battered Women & Co-Author with Angela Y. Davis, Gina Dent and Erica R. Meiners of Abolition. Feminism. Now.

To listen to the uncut interviews, and to get episode notes for this episode and more, become a Patreon partner here.

Prefer to Listen?

Transcript

THE LAURA FLANDERS SHOW

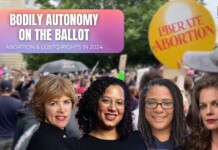

WITH ROE V. WADE UNDER THREAT, IS RADICAL FEMINISM THE ANSWER?

LAURA FLANDERS: In 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court could overturn the landmark decision, legalizing a woman’s right to have an abortion called Roe v. Wade. In so doing, the court would be imperiling all women’s freedoms and creating a new pipeline to prison for the vulnerable, just as the world is learning how counterproductive most incarceration solutions are. Today’s guests argue that things could have been very different if the white dominated, so-called choice movement had paid closer attention always, to all women’s choices or lack thereof, or if the anti-violence movement had rejected criminalization and incarceration as the solution to the violence in women’s lives. Things could have been different, our guests argue, if a different part of the U.S. women’s movement had received more attention, attention it’s just now beginning to get. There’s always been such a movement they argue, because they were there. Today we talk to black abolitionist feminist, Beth Richie, and queer Southern feminist, Suzanne Pharr. They have worked together for abolition, feminism and systemic change for 40 years. What have they learned? What is their message for us now when so much hangs in the balance? Beth Richie is the head of the department of criminology, law and justice and professor of Black studies at the University of Illinois, Chicago and co-author, with Angela Davis, Gina Dent, and Erica Meiners, of “Abolition. Feminism. Now.” which is just out this week from Haymarket Books. Suzanne Pharr, long-time Southern organizer and coach of generations of movements, has just released this fall, her own critically important book called “Transformation: Toward a People’s Democracy” which is out from Virginia Tech Publishing and available for free, for all, as a download. Beth, Suzanne, welcome to the show. I couldn’t be happier to be bringing you to this audience. Let’s start with you two knowing each other. You’ve known each other a long time, right? Suzanne, you wanna kick off, tell us a little bit of the story.

SUZANNE PHARR: I think we’ve known each other almost 40 years, which is a wonderful gift to have a movement friend and a beloved, good friend as well. And I think that’s what movement gives us. And we came together in the creation of a structure for what we called the battered women’s movement, but now call, gender violence, in an effort to end gender violence. And one of the things we were discovering was how much violence there was against women and what we also were discovering, something that we knew in our bones, but I don’t think that we had fully recognized, was that male authoritarianism was part of the whole structure around racism, gender violence, economic exploitation, and began to realize that this had to be confronted. The other thing that was rising during that time was radical black feminists. And so these enormous numbers of pieces of information were coming forward at that time. So then I meet Beth.

BETH RICHIE: Right, Suzanne and I were at a meeting on different sides of the room, and looking at us and hearing our biographies we came from really different places, quite literally and biographically, in terms of geography, in terms of age, race, so many differences between us, and there at least, I felt Suzanne like a kind of immediate connection. Not around those things that were so different, but around a shared political commitment to bringing together feminism, a commitment to ending gender based violence and appreciation for even a lifting up of Black radical feminism. I think we’re coming back to that place, that space where Suzanne and I met each other. I think we realized that a lot of what has happened in terms of feminist organizing has been narrow. It’s been siloed. It’s been co-opted if you will, by the pressure to be legitimate, to have lots of people identify as a feminist. I think we’ve lost our radical edge in some ways and we’ve lost our ability to look across a room and see someone who’s so different from us politically and biographically, and say, we can be in coalition together. In fact, we have to be in coalition together if in fact we’re gonna make change.

LAURA FLANDERS: You, Suzanne, talk about work that is domesticating versus work that is liberating. So do you think our movement to protect or organizational work to protect Roe v. Wade, reproductive rights per se has been domesticated in that sense, Suzanne?

SUZANNE PHARR: I think the work has been more about providing abortions than it has creating the freedom of our bodies. Of really looking at body integrity, pushing the argument that this body is all that we own. This is where . . . Do we have freedom or not? If you don’t own your body, what else do you own? If you cannot have the management of what that body is going to do and have, where does freedom lie? And so I think that the concentration on the Supreme Court, is a concentration just on the delivery of abortions is good, but not enough.

LAURA FLANDERS: And here we have a situation with a Supreme Court justice saying, it’s no imposition for a woman to carry a baby to term and then just deposit that child at a fire station.

BETH RICHIE: I would completely agree with Suzanne. I think on the one hand as feminists, I wanna say as abolition feminists, we have to take care of the legislative process that would guarantee our rights. We have to do that. But it is not enough because if we rely only on the state to set us free, we will not be free. I mean, the state’s interest in controlling our bodies and our money and our movement across borders and everything about our life, has to be part of what we think about as the feminist, the radical feminist led by Black feminism I wanna say, agenda. So, I think we have to be careful about what we think of as abolitionists, as reformist reforms. How do we make the legislation a little bit better, so that a few more women have access to abortion? How do we do that in a way that says we are out here doing radical work. We can’t concede to sort of mainstream arguments. I talk in my work about how we won the mainstream as feminists but we lost the radical movement. And winning the mainstream, will only get us to the place where we are now with Roe, where we can’t say, separate from legislative protection, what are we doing about freedom? That has to be our driving question. It’s both and. It’s not either or but it has to include the more radical work.

LAURA FLANDERS: These have been hard decades going from the ’70s to now. And the few victories there have been, call it Roe v. Wade as one, we haven’t yet talked about the Violence Against Women Act and hate crimes legislation but the few things that have been passed that people, particularly in mainstream, white, middle-class people claim as victories, have been the focus of a defensive movement. And in the meantime, those were never the ideal goals of the movement that you represent and that you’ve been part of, and yet, it has been very hard to articulate that other vision, while there’s been this defensive battle going on. And in a sense, I feel that that’s where we are again today. Although Beth, you were suggesting that you felt there was something really new in this moment as talk of abolition feminism becomes more popular, as talk of mutual aid particularly in a pandemic becomes more understandable to more people. What do you think we need to shed in this moment? And very bluntly, will you be grieving if Roe v. Wade is indeed overturned?

BETH RICHIE: So I move between grief and joy. I think many of us do during this time. We have witnessed and endured just things that we never imagined would be possible. And that’s the good and the bad news I think Laura, like on the one hand, I feel like we lost our inability . . . We lost our ability to look at state violence as part of gender based violence over the years. I think that’s led to an increase, I think increase in mass criminalization and incarceration. I think the anti-violence movement had something to do with that because we didn’t critique carceral responses; in fact, we aligned ourselves with the criminal legal system.

LAURA FLANDERS: Meaning just we accepted or the anti-violence against women movement accepted that the solution to violence against women was incarceration of people committing violence.

BETH RICHIE: More policing, more surveillance, longer sentences, domestic violence courts, all of those things, the Rape Shield Act, all of those registries, sex offender registries, all of those things that might create moments of immediate safety for a person in crisis, but ultimately feed and fill up the spaces of carcerality that work against us. And that meant that we weren’t in a position to work in solidarity with reproductive justice movements, or healthcare movements for all people that would have blessed us in a very different position around COVID, or with anti-violence organizations so that when there was a racial justice uprising, anti-violence folks should have been at the front of the line of those protests, right? That we siloed ourselves because of our alignment with carceral solutions. I think it’s changing. I really do. And I think one of the reasons it’s changing is ’cause there are organizations like INCITE! like Gen Five, organizations all around the country, Creative Interventions. I could name them. We talk about them a lot in “Abolition. Feminism. Now.” They’re not winning their campaigns all the time, but they’re struggling and fighting and bringing a different kind of analysis, a different kind of opportunity to organize.

LAURA FLANDERS: Suzanne?

SUZANNE PHARR: I think that we’re at a place where we have to kind of protect and defend and build at the same time. I think it’s not just a fight that’s here. There’s a lot of protection that we have to do but we really have to build. And I don’t think we can build in the way we’ve been building. I think we still suffer terribly, from the myth of scarcity, that there is not enough to go around if somebody else gets something, it’s gonna be taken from me as opposed that we’re going for the whole. So I do think that we’re at this great moment, the possibility of seeing us as a collective, seeing our lives as terribly linked to each other. For example in COVID, this idea that I may not have it, but I could carry it to you, that we ask as people, ask people to see. But I think we’re gonna have to shed a lot. And a lot of that is gonna have to be in the realm of competition. I think you can’t build movement with groups in competition with each other. And that’s one of the other things that the whole nonprofit industry brought us, is competing for money and then you make your work compete with each other. So you got two levels of competition there that make you not join together to make something larger. We’re at the point that we have to join together or die and not just because of COVID, but–

LAURA FLANDERS: And how do we make those alternatives? And why was the Arkansas Women’s Project historic?

SUZANNE PHARR: Well, knew it. That sets me up to say, oh, we had the answers but that’s not quite true. But I think it was historic because one, starting in 1981, that we were determined that we would work on against sexism, against racism and economic exploitation and we would always combine those three. Particularly we would never talk about one without talking about the other. So we wouldn’t take just a narrow approach and that we would be a multi-racial organization in Arkansas. And it was unique for here, but it was certainly unique also for elsewhere in the country. And we focused on people on the ground, in bringing in all of the people into this group to have a place, to have a home and to be working on the problems that they named. I can’t tell you it was a learning school for us, but coming out of that, there were two things happening. One, the right-wing was rising and becoming more and more visible in Arkansas. And so we were monitoring that. We connected ourselves with the Center for Democratic Renewal in Atlanta, and we were monitoring the clan, not just the clan taught us that skinheads, the covenant sword, arm of the Lord, and exposing them to the public and also trying to do a protest against them. So that was happening on one hand and on the other hand, we were seeing violence against all kinds of people. So we thought it was not just the far-right. It’s the racial violence. It’s the violence against women, violence against queers, violence against religious minorities. So we said, well, we should be monitoring them. Why don’t we just deal with the far-right? That’s not the biggest issue. Everyday lives, those are the biggest issues. And so we would monitor those, suddenly we realized, we set up little groups around the country, the whole state so they sent us newspaper clippings of what the violence was. And we didn’t accept any information except clippings because we knew that people wouldn’t believe. That is the only way we needed to make it authentic. And so when we got those, we created a report and what we found was far more women were experiencing violence. We couldn’t even report it. And so we decided we’d report only the murders of women because they were so extreme. And we wrote a report where we gave every detail, her name, where she was killed, how she was killed, who killed her, whether the children were there, whether her body was abused, whether she had clothes on, you know, all of those details, then how it ended up, did this person go to jail, did they ever find the person, all of that then we gave it back to the public. And so people developed a tremendous consciousness of the kind of violence that women experience. And so I think the answer to your question is, it’s work on the ground I think that will lead us through this.

LAURA FLANDERS: I really encourage people to check out the book, “Transformation” and the download is available for free. Because you have an important distinction that you made there in the area of hate crimes to talk from the individual to the system, to the society that maintains the regimes of violence that we’re really talking about whereas our media likes to talk about the individual at the end of that long chain. You’ve laid out so many of the pitfalls that we’ve fallen into many of our organizations. And certainly I hear the failures of our media to do that job of connecting anyone to anyone. Beth, talk to those who say, okay, well this is very good and you’re doing important grassroots work that will pay off in generations, but right now my hair’s on fire because our rights to an abortion hang in the balance, we have an election coming up, we just need to vote for the least worst and the planet’s on fire.

BETH RICHIE: I think for me, you know these feel like emergencies but in fact, there’s a long history both of how we got to where we are, and resistance against those forces. And I think one thing we need to do is understand this is long-term struggle, even though there’s a vote coming up, right? And we need to be able therefore to think of a long-term strategy and a short-term strategy. We need to try to win and we need to put all of our best thinking and our best organizing toward winning whatever the campaign is. And we need to think long term, how does this campaign fit within a broader agenda of creating the world we wanna live in? That’s the abolition piece. What is it that we want beyond fighting for rights or putting out fires? But what broader issues have changed do we wanna be involved in? And once we sort of give enough energy to both of those spaces, I think we need to recommit to on the ground grassroots, local support like Suzanne described. I mean, yesterday’s consciousness raising is today’s mutual aid in some ways.

SUZANNE PHARR: That’s right.

BETH RICHIE: And it means that we have to find ways to put ourselves in the space of caring for each other, building communities. And I think, when people hear building communities, they think building in Black and Brown communities where people . . . I mean building communities everywhere. If one thing we’ve learned, is that isolation can lock you down and sort of tear apart a fabric that you assumed was there even if you didn’t use it. So all people need to be reminded of how important communities are for our life and work to build one, so that we wanna really live it.

LAURA FLANDERS: You have said, and it is repeatedly said that the definitional, one of the sort of core credos of the abolition feminism movement is the belief that another world really is possible. We like to ask people on this program, what experience do you root that belief in? Suzanne?

SUZANNE PHARR: Well, I could say a number of things, but one is around queerness, to go from being a potential felon to having some freedom. Not everything that one would want, but to see that that shift can change. That you can you can move from some place in which you feel forced to be totally invisible in my lifetime, to my age now, in my 80s, to see that there’s space for people to breathe who are queer, who are trans and gender nonconforming. That to me is a line of possibility.

LAURA FLANDERS: Beth?

BETH RICHIE: I would say two things. One is for me, the kind of every day abolition, the ways that people are keeping each other safe, the way that we have campaigns, that women are coming out of prison when they were sentenced to life for saving their own life and they’re coming out and they’re being held by small groups of people, some formal and some informal and saying, you’re ours now, we got you. We’re not gonna let that happen again. We took care of your kids while you were there. Welcome home. And home is a different kind of place than the one you left where you were so badly hurt, right? So I see small acts like that. I mean that’s not small, that’s big, right? But they don’t sort of appear like as abolition news but we are taking care of each other. We really are. And I see the campaigns against criminalized survivors, as one example of that. All around the country we’re doing that. And I think the other place Laura is really where we started, that Suzanne and I for 40 years, 40 long years, have not only done work, but we’ve changed the work that we’ve done. We’ve gone back and redone some things that didn’t work out so well, that we brought other people into the community of our friendship, that we’ve celebrated each other’s lives, as well as supported each other’s work. I think that’s . . . I don’t often think of friendship as a resistance, but I do think that there really is something about the possibility that our relationship with each other represents for people. And that’s why I so appreciate you inviting us both to be on the show, because I think that there is something here about what the possibility is. A lot of people would have said, “That’s impossible. Those two, no.” My parents would not have thought it was possible for example, that a white Southerner from Little Rock, Arkansas could be one of my dearest friends. They wouldn’t have thought it was possible but look at where we are.

LAURA FLANDERS: Well, I think we should tell more of these stories more of the time. So we will continue to commit to that. And I wanna thank you two so much for being with us.

How do some ideas get traction and others remain marginal on the sidelines? Well media have a huge role to play, Go back 50 years, the height of the 1960s and ideas like greed is good or voting is dangerous, were marginal at best. It was years of repetition by right-wing media outlets collaborating, that made those ideas and the people that voiced them central to our politics today. So two ideas like abolition feminism may have once seemed marginal, barely a whisper, but today they are gaining traction. An independent media like this program and public television and other non-commercial media outlets, are a big part of why. Could things have been very different today? Absolutely. Could they be different still? Well perhaps if we learn the lessons of collaboration. So in that spirit, I want to tell you that there’s a full length interview with Beth Richie, Gina Dent, Erica Meiners and Angela Davis, about their new book right now on Democracy Now! And to remind you, that the full uncut version of my conversation with Beth and Suzanne is available as a download as a podcast, from our website. Thanks for joining me. I’m Laura Flanders, till the next time. Stay kind, stay curious.

For more on this episode and other forward-thinking content and to tune in to our podcast, visit our website at lauraflanders.org and follow us on social media at The LF Show.

Want More Coverage?

You can find more LF Show coverage on movement strategy and history here.

Accessibility

The Laura Flanders Show is committed to making our programming, website and social media as accessible as possible to everyone, including those with visual, hearing, cognitive and motor impairments. We’re constantly working towards improving the accessibility of our content to ensure we provide equal access to all. If you would like to request accessibility-related assistance, report any accessibility problems, or request any information in accessible alternative formats, please contact us.